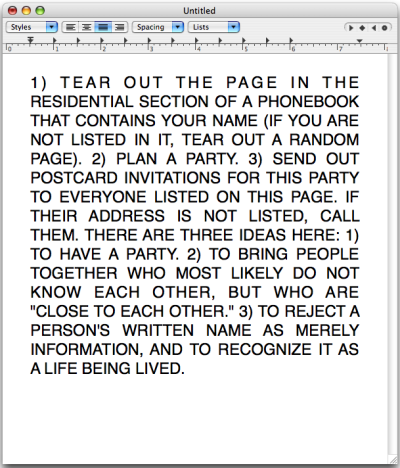

I discovered David Horvitz's idea subscription page a while back and forgot about it, only to rediscover it tonight while I'm trying (not) to study for Monday's biochem exam. It was the perfect inspirational break. David Horvitz posts or sends out a set of instructions almost every day. They're usually very simple but inspiring and surprising, and definitely worth a look. He'll even snail-mail them to you for a small fee.

I wasn't really struck by this one until I got to the last purpose: "To reject a person's written name as merely information, and to recognize it as a life being lived." I've actually been thinking about that idea a lot lately for some reason. The complexity of the world sneaks up on my every now and then, especially when I'm exploring an unfamiliar place with people that I've never met before. It's staggering to think that the earth is filled with almost 7 billion people, each with their own complete life full of problems and connections to everyone else in the world. We spend our entire lives weaving a web of connections, friendships, hurdles and solutions, loves, hatreds, and every single other person in the world does the exact same thing while they occupy the earth. You'd think that the time-space continuum would get saturated with all of the feelings and just explode.

The thought came back to me yesterday when I was reading an article in The New Yorker (by Jonathan Harr--"Lives of the Saints") about aid workers in Chad. It was a heartbreaking account (as they all are) of refugee camps and the constant struggle to keep them safe and functional. At one point the coordinator of a relief organization said, "People tend to treat them as a group, one more camp of twenty thousand refugees. But they have names, hopes, lives, loves. You have to see them as individuals." Even in a war-ravaged country such as Chad, where people have to live six to a tent and have few to no possesions and precious little freedom, every single person has a head full of thoughts and dreams just as complex as the ones that occupy my selfish little brain each day. Each life is different and unique and precious, and that's just amazing.

I guess it's easy to forget that sometimes, especially when you spend your day looking at diseases, symptoms, and statistics in place of patients' names and identities. The first two years of medical school are usually full of book learning and facts and very little actual patient interaction. But someday, our offices will be filled with all of those people out there, each one with their own journey that got them this far. I feel so lucky to be going into a field where I can meet so many different lives.

Anyway, check out the blog. It's full of neat things like that. And he invites you to take them and spread them through the world, because ideas are free and should be shared. Pretty super guy.

The thought came back to me yesterday when I was reading an article in The New Yorker (by Jonathan Harr--"Lives of the Saints") about aid workers in Chad. It was a heartbreaking account (as they all are) of refugee camps and the constant struggle to keep them safe and functional. At one point the coordinator of a relief organization said, "People tend to treat them as a group, one more camp of twenty thousand refugees. But they have names, hopes, lives, loves. You have to see them as individuals." Even in a war-ravaged country such as Chad, where people have to live six to a tent and have few to no possesions and precious little freedom, every single person has a head full of thoughts and dreams just as complex as the ones that occupy my selfish little brain each day. Each life is different and unique and precious, and that's just amazing.

I guess it's easy to forget that sometimes, especially when you spend your day looking at diseases, symptoms, and statistics in place of patients' names and identities. The first two years of medical school are usually full of book learning and facts and very little actual patient interaction. But someday, our offices will be filled with all of those people out there, each one with their own journey that got them this far. I feel so lucky to be going into a field where I can meet so many different lives.

Anyway, check out the blog. It's full of neat things like that. And he invites you to take them and spread them through the world, because ideas are free and should be shared. Pretty super guy.

2 comments:

My favorite of all of Holly's doctors was the one that acted like you're describing: Alan Mathew. He was Indian, studied in England, and cycled. We know because he came in on his day off in his bike cleats and spandex to talk to Holly and see how she was. He came to her funeral, and he cried. He earned a permanent place in our families favor for these things.

said...

What a cool concept. Though I would never have the guts to call random people and invite them to a party it is really cool to actually sit and think that each of those names has their own complete life, history, hopes, dreams, happiness, sadness, etc.

I thought about that while at Disneyland the last time I went. Instead of thinking as the mass of people as an annoying crowd I stopped to think that each family I saw is unique with their own background.

Post a Comment